Our brains have evolved over millions of years and over that time, developed mechanisms that helped us survive different challenges. However, the changes we make in the world aren’t accompanied by evolutions in our brains – our technological development happens too quickly for our bodies to catch up!

Here I want to mention one example of that.

Until not so long ago, the only way we moved was when we ourselves walked/ran. What allows us to move like that and not being confused with the changing visual scenario is a teamwork of our vestibular and visual systems.

We know our eyes are responsible for seeing and belong to what we call visual system. But how about the vestibular system? It’s one of those things in life we don’t notice unless there’s something wrong with them. Here’s a brief introduction.

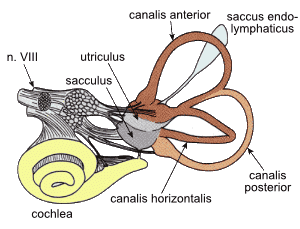

The vestibular system allows us to keep our balance. It’s located in the inner ear and is composed of three semicircular canals and the otoconial organs:

- The semicircular canals sense rotational movements (like when we rotate our heads or drive around a roundabout).

- The otoconial organs sense linear accelerating forces (like running forward or falling down).

Image credit: vestibularSystem_la by Thomas.haslwanter, CC BY-SA 3.0

It’s pretty amazing that the semicircular canals can be seen in dinosaur skulls too – it’s a really ancient system!

When the visual and the vestibular systems agree on what’s going on, we feel fine. However, if the visual system senses we’re still and the vestibular system senses we’re moving, then there’s sensory mismatch. That’s thought to cause motion sickness in some people.

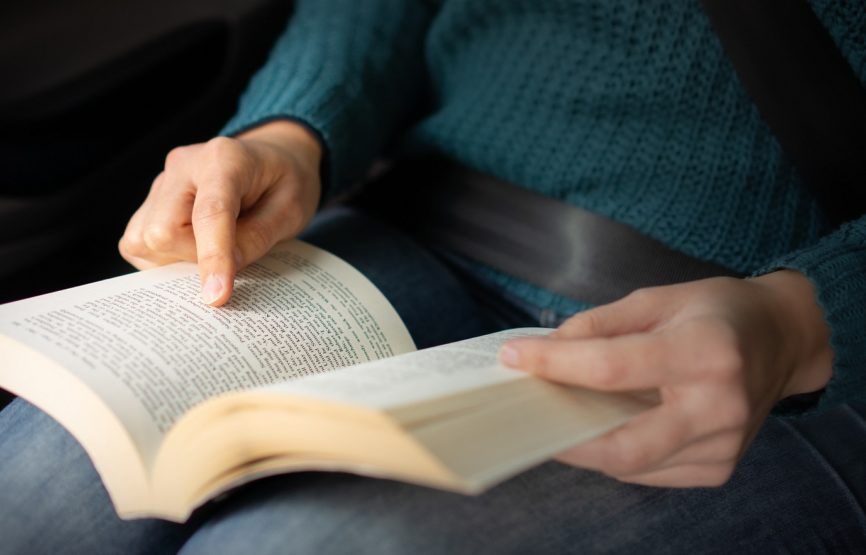

That happens when we read a book in a moving car: the eyes inform the brain that we’re still, since we’re focusing on the text, but the vestibular system will send information about the different accelerations the head is subjected to, because the car is moving. This mismatch only happens with modern inventions, like:

- the means of locomotion we’ve invented, that is, when a person is carried instead of being the one moving or

- videos that give us a visual input of motion that doesn’t match our actual movement.

This is just a simple example of how our brain can’t always keep up with our inventions. For all humans to have a brain that allows us to ride our cars and read without getting sick, all people that get nauseated in the car would have to actually die or be infertile, so that they couldn’t pass on their genes. Of course, that’s ridiculous, but this illustrates nicely how the brain has evolved mechanisms that are constantly being challenged by our inventions.

We’re living with this “old” brain that serves us well most of the time, but often we aren’t aware of the caveats that might be causing us trouble now or might cause trouble in the future.

| References |

|---|

| Video: The vestibular system, balance, and dizziness from Khan Academy 6-minute video explaining the vestibular system. |

| Wikipedia entry on motion sickness Contains explanations and descriptions of the different kinds of motion sickness. |

| Chapter 18 ‘The Vestibular Sense’ of Peggy Mason’s book ‘Medical Neurobiology’ from 2011 In this chapter, Dr. Mason discusses the vestibular sense in-depth. She also mentions motion sickness and how “the vestibular system has not evolved to catch up with the recent development of passenger vehicles”. |

| Wikipedia entry about dinosaur senses Quite short entry, but the semicircular canals are mentioned |

| Article: ‘Evolution of the Vestibular System’ from Werner M. Graf that appeared in the Encyclopedia of Neuroscience (Springer) in 2008 In depth study that makes clear how ancient this system is: “The early appearance of a viable and up-to-date conserved vertebrate vestibular system, in tandem with systems of similar geometry in certain invertebrates may suggest that close to ideal physical solutions developed early in vertebrate history.” |